Archaeologists in South Africa have discovered the footprints of Homo sapiens dating to 153,000 years ago, the oldest known tracks attributed to our species, a new study finds.†

The record-breaking finding is one of many unearthed in Africa over the past few decades. Since the report of 3.66 million-year-old footprints at the site of Laetoli in Tanzania over 40 years ago, paleoanthropologists have found increasingly than 100 walking trails preserved in rocks, ash and mud left by our hominin ancestors, the group that includes modern and extinct humans as well as our closely-related ancestors.†

Seven archaeological sites with tracks left by humans tabbed ichnosites were discovered just east of the southern tip of the African continent, tens of miles inland from the warmed-over coast. In an vendible published April 25 in the periodical Ichnos, an international team of researchers used optically-stimulated luminescence (OSL) to icon out when the impressions were made.†

These South African ichnosites included four with hominin tracks, one with knee impressions, and four with ammoglyphs a term denoting any pattern, not just footprints, made by humans that has been preserved over time.†

Footprint vestige can add a unconfined deal to the archaeological record, equal to the researchers, as it "can provide not just an indication of humans travelling wideness these surfaces as individuals or groups, but moreover vestige of some of the activities that they engaged in," the authors wrote in the study. In South Africa, early vestige for modern human policies includes personal tiara such as jewelry, minutiae of intricate stone tools, the use of utopian symbols, harvesting of shellfish, and coastal grotto and rock-shelter sites.

Related: Massive, 1.2 million-year-old tool workshop in Ethiopia made by 'clever' group of unknown human relatives

The researchers used OSL to stage the South African track sites. This dating method works by estimating the time that has passed since grains of quartz or feldspar in or near the fossilized trackways were last exposed to sunlight. When surfaces that humans walked on were quickly buried, OSL can be used to icon out the date.

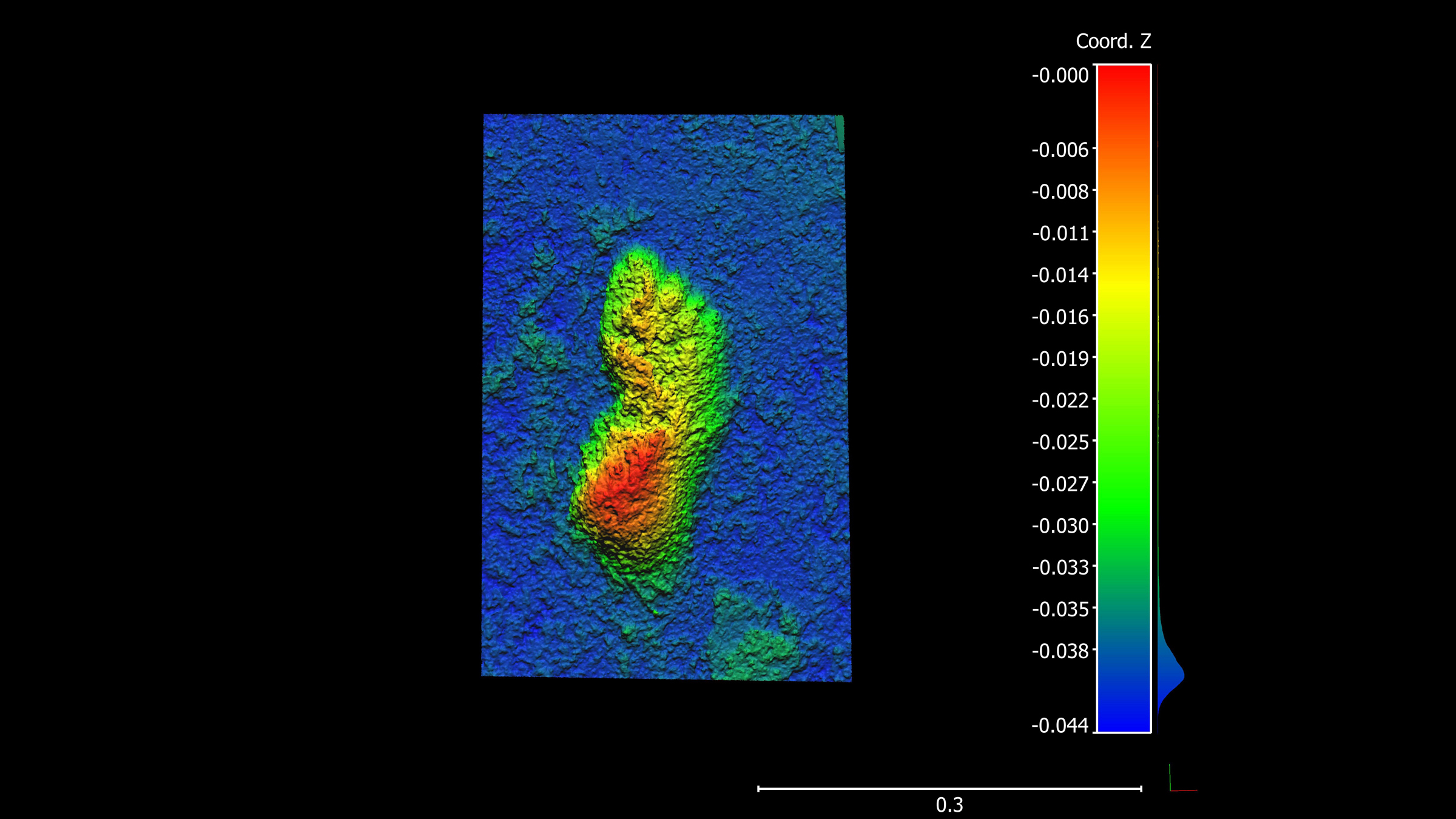

Samples from the Garden Route National Park (GRNP) track site, which contains seven identifiable tracks preserved in upper cliffs, were dated to 153,000 years ago, plus or minus 10,000 years. Although there are older preserved footprints from other hominin species throughout Africa, Asia and Europe, the GRNP track site is now the oldest one made by Homo sapiens, which evolved in Africa virtually 300,000 years ago.

Most of the samples the team examined dated to between 70,000 and 130,000 years ago, and they were "pleasantly astonished" to find the 153,000-year-old track site, study first tragedian Charles Helm, a research socialize at the African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience at Nelson Mandela University in South Africa, told Live Science in an email.†

The discovery has "acted as a spur to protract our search for hominin tracks in deposits we know are plane older," Helm said.

Modern humans arose without 2 unshared groups in Africa mated over tens of thousands of years

Modern humans migrated into Europe in 3 waves, 'ambitious and provocative' new study suggests

Unknown lineage of ice age Europeans discovered in genetic study

The researchers note, however, that attribution of the tracks to a specific species is based increasingly on archaeological artifacts and skeletal remains than on the shape of the tracks themselves. "Not all sites provide conclusive evidence," they wrote in their study, so "controversies and debate are likely to continue."

But the clock is ticking on studying these sites. "We suspect that remoter hominin ichnosites are waiting to be discovered on the Cape south coast," Helm and study co-author Andrew Carr, a physical geographer at the University of Leicester in the U.K., wrote in The Conversation. "They are moreover vulnerable to erosion, so we often have to work fast to record and unriddle them surpassing they are destroyed by the ocean and the wind."